The blood never really washes out, does it? It seeps into the floorboards, stains the concrete, and burns itself into the collective memory of a community that has been hunted, beaten, and slaughtered for the simple fucking crime of existing. These massacres represent more than just body counts—they are the concentrated essence of centuries of hatred distilled into moments of pure, murderous rage against people whose only sin was loving differently, expressing themselves authentically, or simply seeking a goddamn moment of peace in a world that wanted them dead.

Each of these atrocities carved deep wounds into the LGBTQIA+ psyche, wounds that still weep today. They remind us that our joy is always borrowed time, our safe spaces are never truly safe, and our very existence is a political act that some fuckers will kill to silence.

12-06-2016: Pulse Nightclub Massacre - Orlando, Florida

The Latin beat was thumping, bodies were moving, and for a few precious fucking hours, Pulse was exactly what it was supposed to be—a sanctuary. A place where queer Latino bodies could exist without apology, where drag queens could serve looks, where lovers could dance without checking over their shoulders. It was Latin Night, and the club was alive with the kind of joy that our community steals from a world that begrudges us every breath.

Then Omar Mateen walked through the door with enough ammunition to paint the walls red.

At 2:02 AM, he opened fire into a crowd of dancing bodies. Three hours and two minutes later, 49 beautiful souls were dead, 53 others wounded, and the LGBTQIA+ community was left to process the largest mass shooting in American history—targeted specifically at us. The gunman called 911 during the slaughter to pledge allegiance to ISIS, but let's be crystal fucking clear about what this was: a hate crime against queer people, particularly queer people of color, in a space that was supposed to be ours.

The victims' names became a litany of loss: Stanley Almodovar III, Amanda Alvear, Oscar A Aracena-Montero, Rodolfo Ayala-Ayala, Alejandro Barrios Martinez, Martin Benitez-Torres, Antonio Brown—each name a universe of dreams extinguished, families shattered, communities left bleeding. Twenty-three-year-old Angel Colon, who survived despite taking bullets in his hand and hip, later said, "I was crawling for my life." The image of queer bodies crawling through their own blood and the blood of their friends to escape a man who wanted them dead is seared into our collective consciousness.

The psychological aftermath hit the LGBTQIA+ community like a second wave of bullets. Suddenly, every gay bar felt like a potential killing field. Every Pride event became an exercise in hypervigilance. The places that were supposed to heal us—our clubs, our community centers, our gathering spaces—were reimagined as potential crime scenes. Therapists reported massive spikes in anxiety, depression, and PTSD among LGBTQIA+ clients who had never set foot in Pulse but understood viscerally that it could have been them.

The philosophical question that haunted us afterward was simple and devastating: If we can't be safe in our own spaces, surrounded by our own people, celebrating our own joy—where the fuck can we be safe? The answer, as always, was nowhere. Not really. Not completely. The massacre at Pulse reminded us that homophobia and transphobia aren't just slurs or discriminatory laws—they're active death wishes, and some people are willing to pull the trigger.

05-11-2022: Club Q - Colorado Springs, Colorado

Club Q was hosting a drag show and preparing for Transgender Day of Remembrance when Anderson Lee Aldrich walked in with a gun and a head full of the same anti-LGBTQIA+ poison that's been spreading like cancer through American political discourse. It was supposed to be a night of celebration and remembrance—drag performers serving artistry, families supporting their LGBTQIA+ kids, and a community coming together to honor those we've lost to transphobic violence.

Instead, it became another fucking crime scene.

Five people were murdered: Daniel Davis Aston, 28, a transgender man and bartender; Kelly Loving, 40, a transgender woman; Ashley Paugh, 35, a mother who was there supporting the LGBTQIA+ community; Derrick Rump, 38, and Raymond Green Vance, 22. Twenty-five others were wounded. The gunman was stopped by club patrons—because when seconds count, the police are minutes away, and the LGBTQIA+ community has learned we often have to save our own fucking selves.

This wasn't random violence—it was the logical conclusion of months of increasingly violent rhetoric against drag performers and transgender people. Politicians and pundits had spent the previous year painting drag shows as threats to children, transgender people as predators, and LGBTQIA+ gatherings as sites of moral corruption. They created the cultural conditions that made this massacre feel inevitable, then acted shocked when someone took their eliminationist rhetoric to its natural conclusion.

The psychological impact was compounded by the timing—just days after the midterm elections where LGBTQIA+ rights were a major campaign issue, in a state where anti-LGBTQIA+ sentiment was already high. For transgender people especially, Club Q felt like a preview of coming attractions, a glimpse of what political rhetoric looks like when it's translated into bullets and blood. The massacre happened as over 300 anti-LGBTQIA+ bills were being considered in state legislatures across the country, making it clear that the violence wasn't an aberration—it was policy by other means.

06-24-1973: Upstairs Lounge - New Orleans, Louisiana

The UpStairs Lounge in New Orleans was hosting a beer bust—a casual Sunday evening gathering in what was supposed to be a safe space for gay men in the Deep South. Someone set the bar on fire, turning it into a death trap that claimed 32 lives in what remains the deadliest attack on LGBTQIA+ people in American history before Pulse.

The victims were trapped on the second floor as flames engulfed the stairwell. Some jumped to their deaths; others burned alive. Bodies were found embracing, people who chose to die together rather than apart. The Rev. William Richardson Larson, an openly gay minister, was found dead at the piano where he'd been playing. Buddy Rasmussen, a customer, died alongside his boyfriend. Their names should be carved into every monument to LGBTQIA+ resilience, but instead, most people have never fucking heard of them.

The response was almost as devastating as the fire itself. Families refused to claim bodies. Newspapers wouldn't print the victims' names. The Catholic Church refused funeral services. Police treated it as a joke, with officers making wisecracks about "fried fruits" while bodies were still smoldering. The fire was likely arson—a deliberate act of mass murder—but it was barely investigated. The message was clear: dead queers don't matter.

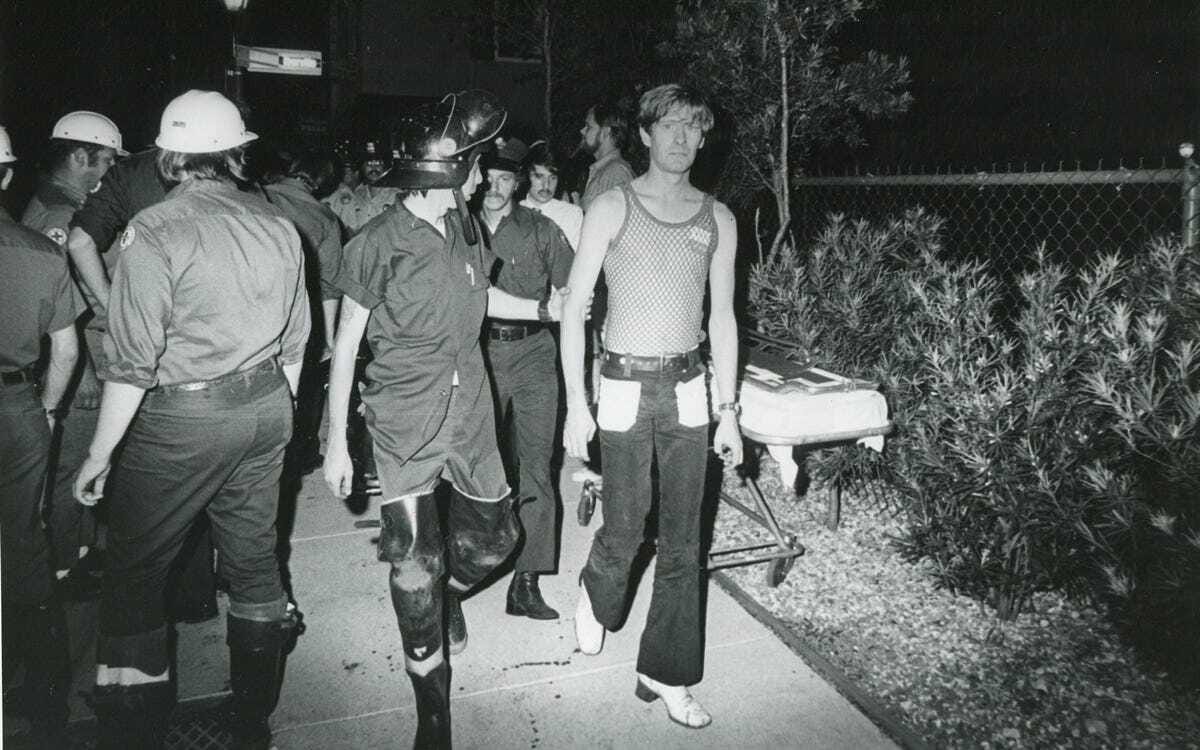

The UpStairs Lounge fire happened just four years after Stonewall, at a time when the LGBTQIA+ rights movement was gaining momentum. The massacre was a brutal reminder that visibility comes with a price, that the more we demanded to exist openly, the more some people wanted us dead. For survivors and the broader gay community, it was a preview of the AIDS crisis to come—a catastrophe that would be met with similar indifference from authorities and similar silence from mainstream media.

The Philosophy of Hatred: Why They Want Us Dead

These massacres aren't random acts of individual madness—they're the logical endpoint of a culture that has been systematically dehumanizing LGBTQIA+ people for centuries. Every religious sermon about "abomination," every political speech about "protecting children," every media representation that portrays us as predators or perverts contributes to a cultural atmosphere where our murder feels justified, even righteous.

The philosophy underlying this violence is simple: we represent chaos to people who need order, authenticity to people who live in fear of their own desires, and change to people who are terrified of evolution. Our very existence challenges the rigid categories that some people need to make sense of the world. We are living proof that gender isn't binary, that sexuality isn't fixed, that families can take many forms, and that love doesn't need their permission to exist.

So they kill us. They kill us in our bars and our synagogues, on our streets and in our homes, because they believe that if they spill enough of our blood, they can wash away the questions we represent. They're wrong, of course—our deaths only multiply the questions, only make our lives more visible, only prove the urgent necessity of our survival.

But understanding their motivation doesn't make the bullets hurt less or the blood run cleaner. It doesn't bring back the 49 beautiful souls who went dancing at Pulse and never came home. It doesn't resurrect the congregation at Tree of Life or the patrons of Club Q or the UpStairs Lounge or the countless others whose names we'll never know because their deaths weren't deemed newsworthy.

What it does is remind us that our joy is an act of resistance, our love is a form of revolution, and our survival is the greatest victory we can achieve. Every day we wake up and choose to exist openly is a day we deny the killers their ultimate victory. Every time we gather in our spaces, love our partners, support our chosen families, and celebrate our authentic selves, we're spitting in the face of everyone who wants us dead.

The blood will never fully wash out, but it waters the ground where new generations of LGBTQIA+ people grow up knowing they have ancestors who fought and died for their right to exist. These massacres are part of our history, but they're not the end of our story. We're still here, still queer, still refusing to disappear no matter how many bullets they fire into our bodies.

And that, more than any revenge, is the most powerful fuck you we can give to those who want us dead.