In the dark fucking ages of American psychiatry, when homosexuality was classified as a mental illness and queer people were subjected to electroshock therapy, chemical castration, and lobotomies in the name of "treatment," Barbara Gittings stood up and said what needed to be said: "We're not sick, you assholes." Born in 1932 in Vienna, Austria, to American parents, Gittings didn't just challenge the psychiatric establishment's classification of homosexuality as pathology—she dismantled it piece by piece with the methodical precision of the librarian she was and the righteous fury of a woman who had spent her entire adult life watching her community be tortured by medical professionals who should have been helping them.

Gittings wasn't content to politely ask for acceptance or quietly hope that attitudes would change. She organized, she protested, she confronted the American Psychiatric Association directly, and she refused to let them continue pathologizing her existence without a fight. When the APA finally removed homosexuality from their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in 1973, it wasn't because they suddenly developed enlightened attitudes—it was because activists like Gittings had made their position scientifically and politically untenable. She didn't just change a classification; she helped save thousands of lives by ending the medical justification for torturing gay people into compliance.

The Making of a Revolutionary: From Confusion to Clarity

Barbara Gittings's journey to activism began in the most American way possible—in a college library, researching her own fucking existence because nobody else would give her straight answers about what it meant to be attracted to women. Born into a middle-class family that moved frequently due to her father's work, she grew up feeling different but having no language or framework to understand why.

When she enrolled at Northwestern University in 1950, she was a typical college student in every way except one: she was desperately trying to figure out why she was attracted to women instead of men. In an era when homosexuality was literally unspeakable in polite society, when the very word "lesbian" was considered so shocking that newspapers wouldn't print it, Gittings did what any good researcher would do—she went to the library.

What she found there was a psychological horror show disguised as medical literature. Book after book described homosexuality as a mental illness, a developmental disorder, a psychological pathology that could and should be cured. The "experts" had a whole arsenal of explanations for why people like her existed—overbearing mothers, absent fathers, childhood trauma, arrested development—and an even more horrifying arsenal of "treatments" designed to fix them.

The psychological impact of reading this shit cannot be overstated. Imagine being a young woman trying to understand herself and discovering that every medical authority in your society considers your very existence to be evidence of mental illness. The internalized shame, self-doubt, and fear that this "research" created in LGBTQIA+ people was devastating and intentional—designed to make them compliant with attempts to "cure" them.

But Gittings had something that many of her peers lacked: a librarian's skepticism about sources and a growing suspicion that the experts might be full of shit. The more she read, the more she began to question whether the problem was with homosexuality or with the people studying it.

The Mattachine Society: Where Polite Activism Met Reality

In 1958, Gittings discovered the Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights organizations in America, and it changed her life forever. But it also pissed her off. The organization, founded in the early 1950s, was committed to what they called "accommodation"—basically, trying to prove to straight society that gay people were just like everyone else, except for that one little detail about whom they fucked.

The Mattachine approach was understandable given the political climate of the 1950s—this was the era of McCarthyism, when being gay could cost you your job, your security clearance, and your freedom. The organization's founders believed that the best strategy was to keep their heads down, be respectable, and hope that straight society would eventually accept them as harmless.

Gittings thought this approach was bullshit, and she wasn't afraid to say so. She joined the New York chapter of Mattachine in 1958 and immediately began pushing for more visible, more confrontational activism. She understood something that the old guard didn't: that respectability politics wouldn't work because the problem wasn't that gay people were too visible—it was that they weren't visible enough.

Her psychological insight was profound: as long as gay people remained hidden, straight society could continue to believe whatever stereotypes and prejudices they wanted about homosexuality. The only way to change attitudes was to force people to confront the reality of gay existence—to see actual gay people living actual lives rather than the pathological caricatures promoted by the medical establishment.

The Daughters of Bilitis: Creating Community Through Visibility

In 1958, Gittings also became involved with the Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian organization in the United States. Founded in San Francisco in 1955, DOB was even more conservative than Mattachine, focused primarily on providing social opportunities for lesbian women in a safe, private environment.

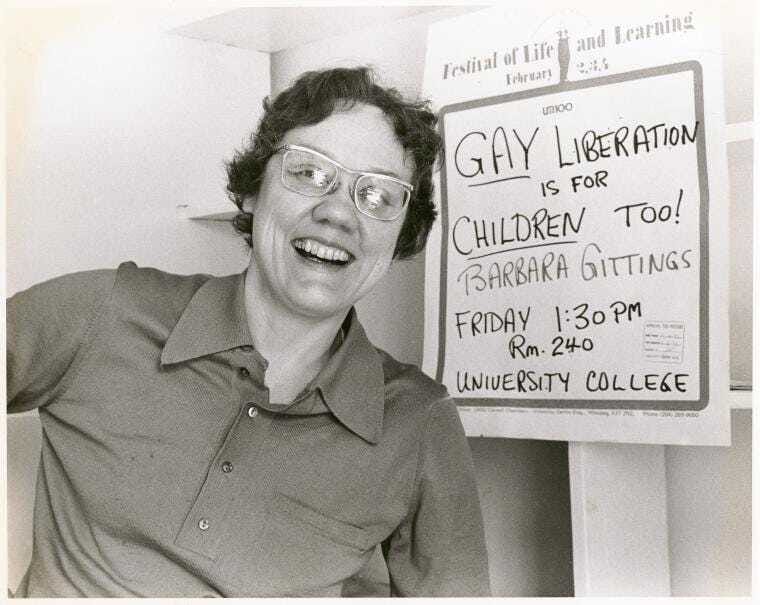

But Gittings wasn't interested in hiding. She became the editor of The Ladder, DOB's newsletter, and immediately began transforming it from a timid publication that avoided anything controversial into a bold voice for lesbian rights and visibility. Under her editorship, The Ladder began featuring photographs of lesbians (with their permission), publishing articles that challenged the medical pathologizing of homosexuality, and providing positive representations of lesbian relationships.

This shift toward visibility was revolutionary in ways that are hard to understand today. In the 1960s, most gay publications featured either no photographs of gay people or images that were so heavily shadowed or cropped that the subjects were unrecognizable. The idea that lesbians would allow their faces to be published in a gay magazine was considered so dangerous that many DOB members were horrified by Gittings's approach.

But Gittings understood the psychological importance of representation. She knew that isolated lesbians across the country were reading The Ladder as their only connection to lesbian community, and she wanted them to see that lesbians were real people with real lives, not the pathological specimens described in medical literature.

The psychological impact of this visibility cannot be overstated. For many readers, The Ladder was the first place they had ever seen positive representations of lesbian existence. It provided both validation and hope—proof that they weren't alone and that other women like them were not only surviving but thriving.

The Confrontation Strategy: Making Homosexuality Impossible to Ignore

By the early 1960s, Gittings was convinced that the gay rights movement's strategy of respectability and accommodation was not only ineffective but counterproductive. She began advocating for what she called "confrontation"—direct, visible challenges to discrimination and prejudice that would force society to deal with gay people as real human beings rather than abstract concepts.

In 1965, she organized the first gay rights picket in front of the White House, protesting the federal government's ban on employing gay people. The images of well-dressed gay men and lesbians carrying signs demanding equal rights were shocking to a society that had never been forced to confront organized homosexual political action.

The psychological courage required for these early demonstrations cannot be overstated. The participants were risking their jobs, their families, their safety, and their freedom by identifying themselves publicly as homosexuals. Many wore sunglasses or otherwise tried to disguise their faces, but they showed up anyway because they understood that visibility was the price of liberation.

Gittings's strategic insight was brilliant: by presenting gay people as ordinary Americans demanding basic civil rights rather than patients seeking treatment for mental illness, she was reframing the entire discourse around homosexuality. She was moving the conversation from the medical model—where gay people were sick individuals who needed to be cured—to the civil rights model—where gay people were a minority group facing discrimination.

The War Against Psychiatric Oppression

But Gittings's most important battle was against the psychiatric establishment itself. She understood that as long as homosexuality was classified as a mental illness, gay people would continue to be subjected to "treatments" that were actually torture, and society would continue to view them as fundamentally defective.

The psychiatric profession's approach to homosexuality in the 1960s was a fucking nightmare. Therapists were using electroshock therapy, aversion therapy (including showing gay men pictures of naked men while administering electric shocks or nausea-inducing drugs), hormone treatments, and even lobotomies to try to "cure" homosexuality. These treatments didn't work—they couldn't work, because there was nothing to cure—but they destroyed thousands of lives and caused immeasurable psychological trauma.

Gittings began a systematic campaign to challenge the psychiatric establishment's classification of homosexuality as mental illness. She studied the research, attended psychiatric conferences, and began confronting psychiatrists directly about their unscientific and harmful approaches to treating gay people.

Her psychological insight was devastating to the psychiatric establishment: she pointed out that their research was fundamentally flawed because it was based entirely on gay people who were seeking treatment or who had been forced into treatment. It's like studying cancer by only looking at people who are dying from it and then concluding that cancer is always fatal.

The vast majority of gay people, Gittings argued, were living perfectly healthy, productive lives without any need for psychiatric intervention. The only reason they might seek therapy was to deal with the psychological damage caused by living in a society that told them they were sick.

The APA Infiltration: Activism from Within

Gittings's most brilliant tactical move was her decision to infiltrate the American Psychiatric Association's own conferences and meetings. Starting in the late 1960s, she began attending APA meetings not as a patient or a researcher, but as an activist demanding that gay voices be heard in discussions about homosexuality.

This was psychological warfare at its finest. Psychiatrists were used to talking about gay people, not to gay people. They were comfortable theorizing about homosexuality in the abstract but deeply uncomfortable being confronted by actual homosexuals who refused to accept their pathological classifications.

In 1972, Gittings organized a panel at the APA's annual meeting titled "Psychiatry: Friend or Foe to Homosexuals?" The panel included both hostile and sympathetic psychiatrists, but the real bombshell was the appearance of "Dr. H. Anonymous"—a gay psychiatrist who spoke from behind a mask and with a voice modulator to protect his identity while describing the discrimination and fear that gay medical professionals faced within their own profession.

The psychological impact of this presentation on the psychiatric establishment was enormous. For the first time, many psychiatrists were forced to confront the possibility that their colleagues—people they respected and worked with—might be gay themselves. It shattered the comfortable distance between the treaters and the treated.

The Victory: When Science Finally Caught Up with Reality

The combination of Gittings's activism, changing social attitudes, and pressure from within the psychiatric profession itself finally led to the APA's decision in 1973 to remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. This wasn't just a bureaucratic change—it was a fundamental shift in how American society understood homosexuality.

The psychological impact of this victory on the LGBTQIA+ community cannot be overstated. Overnight, millions of gay people were no longer officially mentally ill. Parents could no longer force their gay children into psychiatric treatment. Insurance companies could no longer pay for "conversion therapy." The medical justification for discrimination and violence against gay people had been removed.

But Gittings understood that the victory was fragile. She continued her activism, working to ensure that the APA's decision stuck and that other medical and psychological organizations followed suit. She also worked to educate mental health professionals about how to provide genuinely helpful therapy to LGBTQIA+ people—therapy that affirmed their identities rather than trying to change them.

The philosophical implications of this victory were profound. For the first time in modern American history, a minority group had successfully challenged the medical establishment's classification of their identity as pathological. It established an important precedent for other groups facing medical discrimination and provided a model for how activism could challenge supposedly scientific authority.

The Personal Cost of Public Activism

Gittings's decades of activism came with significant personal costs. She faced job discrimination, social ostracism, and constant stress from being a public target for anti-gay hostility. Her relationship with her partner, Kay Tobin (later Kay Tobin Lahusen), was subjected to scrutiny and criticism from both hostile straight society and conservative elements within the gay community who thought she was too visible, too confrontational, too unwilling to compromise.

The psychological toll of being a full-time activist for an unpopular cause was enormous. Gittings dealt with depression, anxiety, and the constant stress of knowing that her public visibility made her a target for violence and harassment. She also faced criticism from within the gay community—from people who thought her tactics were too aggressive and from younger activists who thought she wasn't radical enough.

But she persisted because she understood that the stakes were too high for compromise. Every day that homosexuality remained classified as mental illness, gay people were being subjected to harmful "treatments." Every day that gay people remained invisible, young LGBTQIA+ people were growing up believing they were fundamentally broken.

Her commitment to the cause required sacrificing many of the normal pleasures and securities of life. She couldn't have a completely private relationship, couldn't avoid political controversy, couldn't retreat into the kind of respectability that might have made her life easier but would have betrayed the people counting on her activism.

The Intersection of Library Science and Liberation

Gittings's background as a librarian profoundly shaped her approach to activism. She understood the power of information, the importance of documentation, and the need to preserve the historical record of LGBTQIA+ resistance. Her work wasn't just about changing laws or policies—it was about changing the fundamental narratives that society told about gay people.

She applied librarian principles to activism: careful research, systematic organization, preservation of documents, and broad dissemination of information. She understood that lasting social change required changing not just attitudes but the underlying information systems that shaped those attitudes.

Her work with The Ladder exemplified this approach. She transformed it from a social newsletter into a comprehensive archive of lesbian thought, experience, and resistance. She published articles by and about lesbians from all walks of life, creating a literary and intellectual tradition that had previously been almost completely suppressed.

The psychological importance of this work cannot be overstated. For isolated LGBTQIA+ people across the country, publications like The Ladder were lifelines—proof that they weren't alone, that other people shared their experiences, and that their lives had value and meaning beyond what mainstream society acknowledged.

The Legacy of Confrontational Activism

Gittings's approach to activism—direct, confrontational, unwilling to compromise on fundamental questions of dignity and rights—provided a model for later LGBTQIA+ activists and for other social justice movements. She demonstrated that marginalized groups didn't have to wait for permission to demand equality, didn't have to prove their worthiness for basic human rights, and didn't have to accept expert opinion that contradicted their lived experience.

Her victory over the psychiatric establishment proved that supposedly scientific authority could be challenged and changed when it was based on prejudice rather than evidence. This lesson has been crucial for other communities facing medical discrimination, from transgender people challenging pathological classifications of gender identity to fat activists challenging medical assumptions about weight and health.

The psychological liberation that her work provided to LGBTQIA+ people continues to reverberate today. Every time someone refuses to accept a mental health professional's attempt to pathologize their sexual orientation or gender identity, every time an LGBTQIA+ person demands affirmative therapy rather than conversion therapy, every time someone challenges medical authority that contradicts their lived experience, they're building on the foundation that Gittings laid.

The Continuing Relevance of Information Warfare

In an era when LGBTQIA+ rights are again under attack, when conversion therapy is being repackaged and promoted by religious and political conservatives, when young LGBTQIA+ people are being told that their identities are phases or mental illnesses, Gittings's example remains urgently relevant.

Her understanding that information is power, that representation matters, and that marginalized communities must control their own narratives provides a roadmap for contemporary activism. She showed that it's possible to challenge expert authority when that authority is being used to harm rather than help, and that sustained, organized resistance can change even the most entrenched institutional prejudices.

The psychological principles she identified—that visibility reduces stigma, that community reduces isolation, that accurate information reduces fear—remain as relevant today as they were in the 1960s. Her work reminds us that the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights isn't just about laws and policies—it's about the fundamental right to exist without being pathologized, criminalized, or erased.

The Sacred Act of Refusing to Be Sick

Perhaps Gittings's greatest contribution to LGBTQIA+ liberation was her simple, revolutionary insistence that being gay was not a sickness. This wasn't just a political position—it was a spiritual and psychological stance that transformed how millions of people understood themselves.

By refusing to accept the psychiatric establishment's pathological classification of homosexuality, she was asserting something profoundly important: that LGBTQIA+ people were the ultimate authorities on their own experience, that scientific-sounding prejudice was still prejudice, and that no one had the right to define another person's identity as inherently disordered.

This principle—that marginalized people are experts on their own lives—has become central to contemporary social justice movements. From disability rights activists challenging medical models that pathologize difference to racial justice activists challenging psychological theories that blame victims for systemic oppression, Gittings's example continues to inspire people who refuse to let experts define their experiences for them.

The Revolutionary Power of Saying "Fuck That"

Barbara Gittings's legacy can be summed up in her fundamental refusal to accept bullshit, even when that bullshit came with medical degrees and official stamps of approval. She looked at a psychiatric establishment that was torturing gay people in the name of treatment and said, essentially, "Fuck that. We're not sick, you're the ones with the problem."

This kind of clarity—the ability to see through official rhetoric to underlying prejudice—is what made her such an effective activist. She wasn't intimidated by credentials or authority when those credentials were being used to justify harm. She trusted her own experience and the experiences of her community over the theories of people who had never lived what they were trying to explain.

Her victory over the APA wasn't just a policy change—it was proof that marginalized communities have the power to challenge and change even the most entrenched systems of oppression when they organize, persist, and refuse to accept definitions of themselves created by their oppressors.

The revolution she started continues today, carried forward by every LGBTQIA+ person who refuses to be pathologized, every activist who challenges expert authority that contradicts lived experience, and every individual who understands that the most radical act is sometimes simply insisting on your right to define yourself.

Holy shit, what a legacy: she helped save an entire community from medical torture by having the courage to tell the experts they were wrong. That's the kind of revolutionary clarity the world needs more of—the willingness to trust your own experience, challenge authority that causes harm, and never stop fighting until justice is achieved.